Obituary: Eliot Hearst (1932–2018), Psychologist, Author, and Chess Player

September 10, 2018

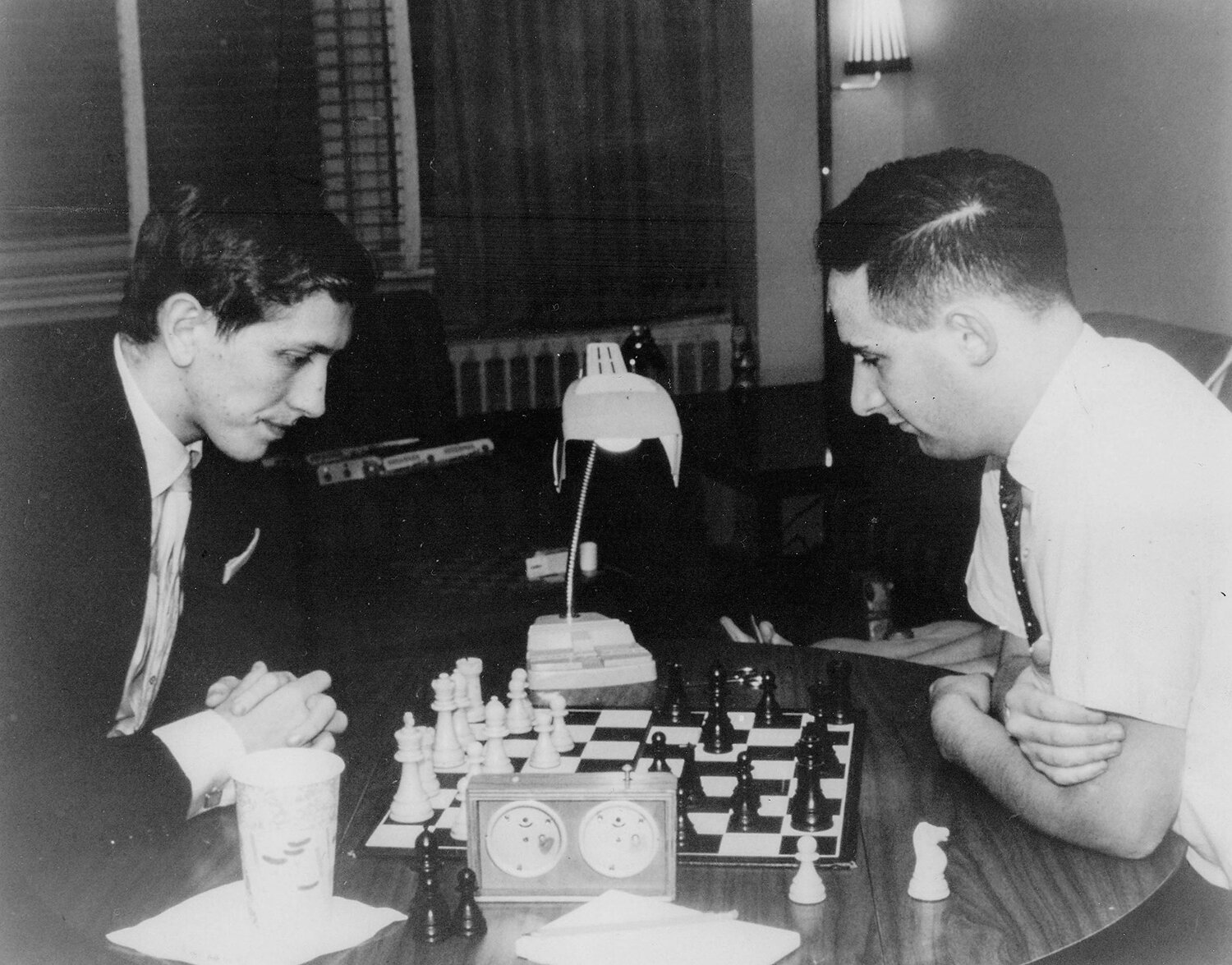

Above: Eliot Hearst, right, playing an informal game with Bobby Fischer in August 1962.

Eliot S. Hearst, the co-author of Blindfold Chess, passed away in Tucson, Arizona, in January 2018. This post contains two obituaries that focus on the twin passions of his life: chess and psychology. The first obituary, by Al Lawrence, appeared in the May 2018 issue of Chess Life. The second, by Hearst’s onetime Indiana University colleague James H. Capshew, focuses on Hearst’s academic psychology career. A shorter version of Capshew’s obituary will soon appear in American Psychologist.

Eliot Hearst: Contributions Deep, Wide and Witty

By Al Lawrence. This article appeared in the May 2018 Chess Life and is posted here with permission of US Chess.

The generations of top American players active in the 1950s and early 1960s are a fascinating mix of personalities and I am nostalgic for them. You read Chess Life, so you know many of the names—from Fine, Reshevsky, and Denker to Evans and Bisguier and of course, Fischer. But you may have missed one of my personal favorites, a 20th-century Renaissance man of culture and wit named Eliot Hearst, whose long and illustrious life ended January 30, 2018, in Tucson, Arizona.

Born in New York City in 1932, Hearst was actually the first notable chess player I ever met, and the one who opened up the real chess world for me. In the late 1960s, he found himself toward the start of his academic career at the University of Missouri-Columbia. To promote the chess club, he gave free simultaneous exhibitions. As I wrote in “My Best Move” (January 2018 Chess Life), knowing nothing about Hearst or organized chess, I was one of his challengers on a freezing night in 1967.

He was already a distinguished full professor of psychology, having completed a bachelor’s degree summa cum laude from Columbia University in 1953 and finishing his Ph.D. in experimental psychology a speedy three years later. He then spent two years in uniform at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, a half-dozen years at the National Institute of Mental Health and a year as a Special Fellow at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. But at our first meeting, he was only the distinguished figure speeding along from board to board inside the rectangle of tables at the Tiger Hotel. More than 40 years later, his emails to me still signed off with “Cheers for Old Mizzou!”

In the years before Missouri, he played a bit of big time chess. He learned the moves in the fifth grade from a teacher. The Manhattan Chess Club rejected Hearst as too young, but, along with contemporary Larry Evans, Eliot garnered the finer points when they were both admitted to the Marshall Chess Club, just missing a first-hand connection with Frank Marshall, who passed away in late 1944. By 15, Hearst was competing in the U.S. Junior and in 1950, still a teen, he won the prestigious New York State Championship ahead of Arthur Bisguier and Max Pavey, making master. He followed up by winning the Marshall Chess Club Championship. He qualified for the U.S. Championships of 1954 and 1961-2, finishing mid-field, and turned down further chances at the title for professional reasons. Perhaps Hearst’s best-known game is his mating-attack victory with black against Bobby Fischer in the 1956 Rosenwald tournament. Yes, Bobby was only 13, but he had just three rounds earlier uncorked his “Game of the Century” against Donald Byrne.

But it was in 1960 that Hearst secured his mooring in the mainstream of American chess history. It was during a time of perilous flareups in the Cold War between the U.S. and the USSR, only a few months after the Soviets had humiliatingly shot down and captured pilot Francis Gary Powers in our “secret” U-2 spy plane and a scant year before the Berlin Wall isolated the Allied sector. As a member of the U.S. squad at the World Student Team Championship, Hearst ventured into a citadel of USSR chess—the Palace of the Pioneers in Leningrad (now again St. Petersburg)—to help commandeer first place ahead of the Soviet team led by Boris Spassky. It was the only time the U.S. has ever won the World Student Team, never before even coming close. And it was the first time since the 1937 Olympiad (the Russians didn’t show up) that any American chess team had won any world championship. “I think a tear or two were shed,” when the Soviet band struck up The Star Spangled Banner, Hearst wrote. The team was feted on its return. Read Hearst’s detailed, first-hand account of his Student Team’s historic victory.

Former Chess Life Editor Frank Brady gave the young Dr. Hearst his own column, “Chess Kaleidoscope.” “I loved it,” Brady said. “He threw everything in there—it was full of commentary and news.” And full of wit as well. In 1964, after Fischer’s still unmatched 11-0 sweep of the U.S. Championship, Hearst wrote that he’d beaten Fischer in 1956, and liked to believe that Fischer hadn’t improved since then. Readers loved it. “It was what made me want to write some day for the magazine,” GM Andy Soltis, the longest-running and most popular Chess Life columnist, told me.

Brilliant and urbane, Hearst didn’t hide a well-tuned sense of the silly. His July 1962 column included his extensive “Gentle Glossary,” with apologies to Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary. Among my favorites:

Good Bishop: your opponent’s bishop.

King’s Indian Reversed: naidni sgnik.

Reshevsky, Sammy: an 80-year-old chess prodigy.

Like several of his 1960 teammates, Hearst left chess. In academia, chiefly at Indiana University but also at University of California, Berkeley, Columbia University, and the University of Arizona, he amassed an illustrious career of notable publications and prestigious honors. In 2009, he brought together his brilliance in two fields to co-author the definitive work on blindfold chess.

Hearst is survived by his sister, Marlys Witte, of Tucson, Arizona; two children, Jennifer, of Berkeley, California, and Andrew, of Brooklyn, New York; and his longtime partner, Elaine Rousseau, of Tucson.

Eliot Hearst’s contributions to chess didn’t end with my selection of highlights. He served three years as a precocious vice president of US Chess, directed many scholastic and local tournaments, and organized the first Eastern Open. He captained successful U.S. international teams that included Fischer.

Hearst’s contributions to our game were deep, wide, and witty.

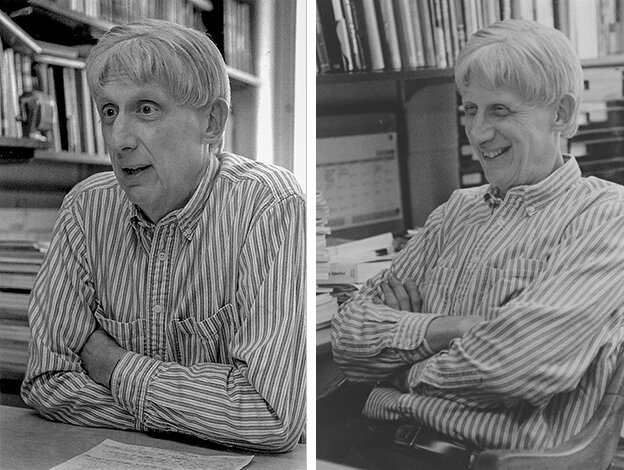

Obituary: Eliot S. Hearst (1932–2018)

By James H. Capshew, Indiana University

Eliot Hearst spent his life pursuing his twin intellectual loves—chess and psychology—and was a remarkable contributor to both. He was a devoted father, raising three children.

Born in New York City, Eliot Hearst spent his childhood, adolescence, and youth gaining experience in that urban mecca, sampling a wealth of cultural opportunities. He became interested in chess at an early age, joining the Marshall Chess Club at age 12, and pursued it seriously throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Among his tournament successes were victories in the Eastern Open, New York State, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C., championships, and several top-5 finishes in U.S. Open tourneys. He had a well-known tournament win over Bobby Fischer, another chess prodigy from New York. Hearst gained the titles of Senior Master and Life Master from the U.S. Chess Federation. In addition, he was the Captain of the U.S. Olympic Chess team (1962), a vice-president of the U.S.C.F., an organizer and director of many tournaments, and a featured columnist for Chess Life in the 1960s. He once remarked that he devoted more time to serious chess than to academic psychology until he was about 30 years old.

Hearst became a psychology major at Columbia University and received his B.A. summa cum laude in 1953. He began the graduate program in experimental psychology as a Harry J. Carman Fellow in 1953-54, served as teaching assistant for Fred S. Keller in the introductory laboratory course, and received his M.A. in 1954. For the next two years, he continued his doctoral training under William N. “Nat” Schoenfeld as a teaching and research assistant. “His vast knowledge of the sciences and humanities was impressive,” Hearst recalled, “and he was the best teacher I ever had.” Hearst’s dissertation investigated effects of time-correlated reward schedules in the pigeon, and was awarded in 1956, only three years beyond his baccalaureate degree. He spent the next two years on active duty in the U.S. Army, stationed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC, where he worked in the departments of experimental psychology and of neurophysiology.

Staying in the District of Columbia until 1964, Hearst was a Senior Experimental Psychologist at the Clinical Neuropharmacology Research Center, a joint unit of the National Institute of Mental Health and Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital. His experimental work expanded to include pharmacological, neuroanatomical, genetic, and biochemical correlates of behavior as well as classical and instrumental conditioning. In 1964-65, Hearst took up a NIMH fellowship at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, under John R. Vane (a future Nobel Prize winner) in the Department of Pharmacology. On one occasion, after dinner at Vane’s residence, Hearst played blindfold chess with Vane as well as his two daughters simultaneously. Returning to the U.S., he was recruited by the University of Missouri, where he was appointed a full professor of psychology. In 1966, he was awarded his first NIMH grant, to study “Basic Processes in Learning and Behavior Change.” His still-ardent interest in chess was on display in the second issue of Psychology Today in 1967, where he contributed a thoughtful review (and the journal cover motif), “Psychology Across the Chessboard.” After five years at Missouri, where he supervised four PhD dissertation students and published over a dozen research papers, he moved to Indiana University in 1970.

At Indiana’s Department of Psychology, he continued his experimentation on conditioning in pigeons, and taught both graduate and undergraduate students, in courses on animal behavior, learning theory, and history and systems of psychology. An approachable yet demanding mentor, he patiently guided hundreds of students, teaching them scientific methods and effective writing techniques. Augmenting his experimental work, Hearst’s reputation for scholarly synthesis and integration was growing, and he published several review essays. In 1974, Hearst co-authored a monograph with Herbert Jenkins that reviewed behavioral studies on the relations between stimulus and reinforcement.

As the centennial of the founding of the first laboratory of experimental psychology—in 1879 at Leipzig by Wilhelm Wundt—approached, the Psychonomic Society commissioned Hearst to organize and edit a major volume containing historical assessments of the major subfields of psychology, written by research scientists. The nearly 700-page book, The First Century of Experimental Psychology, was published in 1979, and contained an introductory essay by Hearst. Garnering positive reviews, the book was reprinted multiple times, including a paperback edition.

Hearst’s expertise in psychology was avidly sought, and he served on several editorial boards between 1963 to 1985 as well as reviewing for many other publications, and he successfully resisted offers to become the editor of other journals in favor of his own writing projects. Elected to the governing board of the Psychonomic Society, he served from 1977-82. During his Indiana years, Hearst was awarded prestigious fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation (1974-75) and the James McKeen Cattell Foundation (1981-82) and was elected to the Society of Experimental Psychologists in 1981. He was a fellow of five divisions of the American Psychological Association: Experimental Psychology, Physiological and Comparative Psychology, Experimental Analysis of Behavior, History of Psychology, and Psychopharmacology.

In 1984, IU honored him with the title of distinguished professor of psychology. The citation noted Hearst’s wide range of topics, including the nature of reinforcement and punishment, discrimination and generalization, learning, cognition, memory, and biological constraints on behavior. “His modus operandi is to enter an area under dispute, identify the critical issues, and, with a few deftly crafted experiments, resolve the principal controversies,” an admiring colleague stated, adding, “this is all the more amazing when one considers the diversity of the topics he has researched.” His penchant for synthetic review was on display again in 1988, when he contributed “Fundamentals of Learning and Conditioning” to the 2nd edition of Steven’s Handbook of Experimental Psychology, an authoritative classic first published in 1951.

Regular renewals of his NIMH grants continued until 1988, until he decided to devote more time to library research and writing, although he continued to have an active lab until retirement. Hearst supervised 10 doctoral dissertations at Indiana and served as committee member for 20 other PhD candidates. In 1988, he spearheaded the organization of the centennial celebration of the IU psychological laboratory and co-edited a centennial monograph containing data on every graduate degree in psychology, lists of faculty and department administrators, and a narrative history.

After 26 years, Hearst retired from Indiana University in 1996, and the department hosted a “Hearst Fest” with a dinner reception that included his former students. Returning to New York, he served as an adjunct professor at Columbia University, his alma mater. He received a grant in 1998-99 from the Harvard University McMaster Fund to study blindfold chess. Moving to Tucson in 1999, where his sister was on the faculty of the University of Arizona, Hearst obtained another courtesy appointment there in the psychology department, where he continued to advise students. Along with a co-author, John Knott, he published his chess magnum opus in 2009: Blindfold Chess: History, Psychology. Techniques, Champions, World Records, and Important Games. The book was well received in the chess world, and Hearst wrote occasional blog postings on blindfold chess into his 80’s. After a brief illness, Eliot Hearst died in Tucson on January 30, 2018, at 85 years of age.

The contributions of Eliot Hearst to Indiana University and to scientific psychology will be commemorated through an endowed professorship in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, generously funded by Hearst and given in memory of his daughter, Nicola Jane Hearst (1971-1999).